Works from the loft

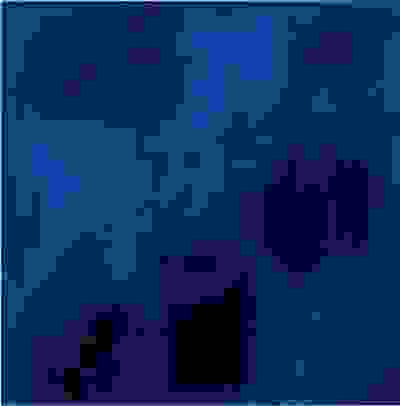

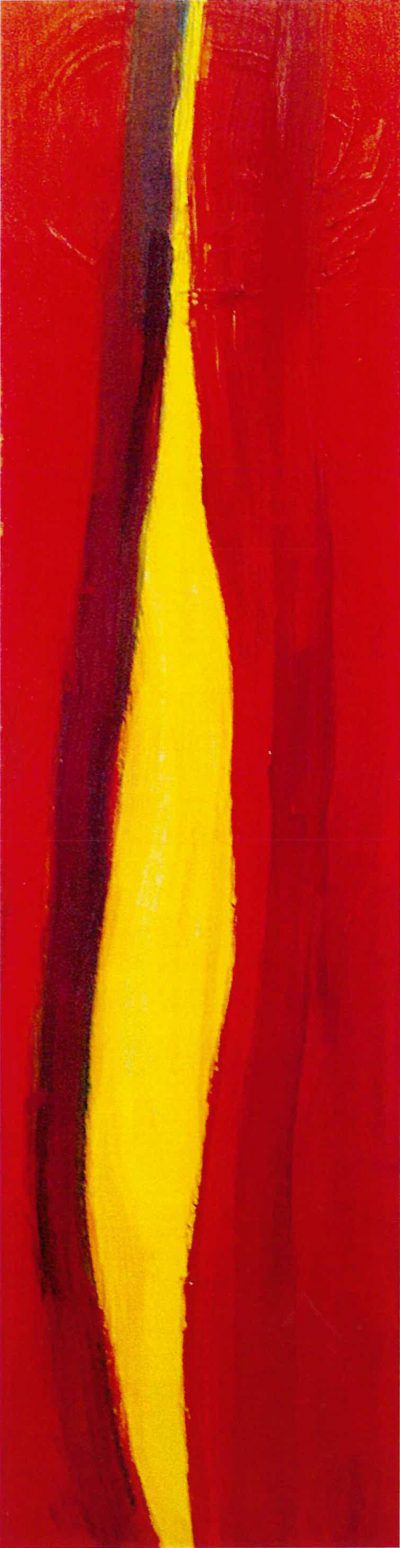

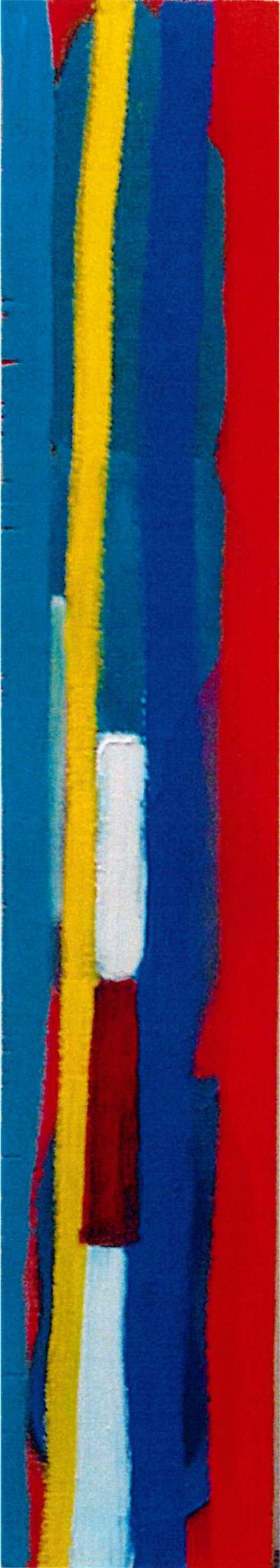

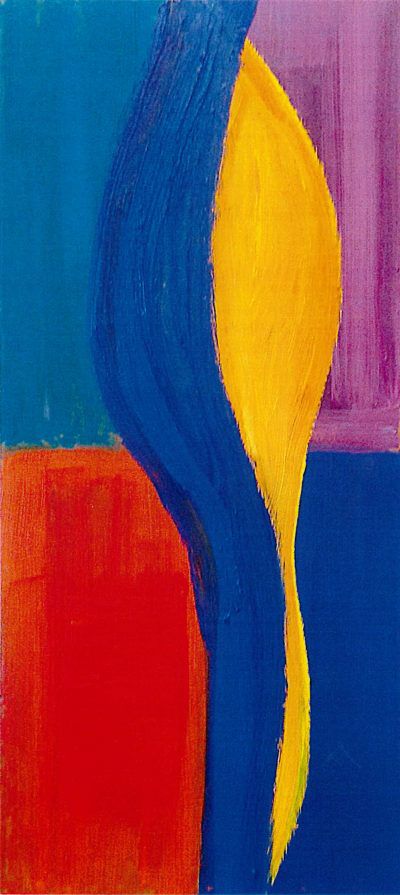

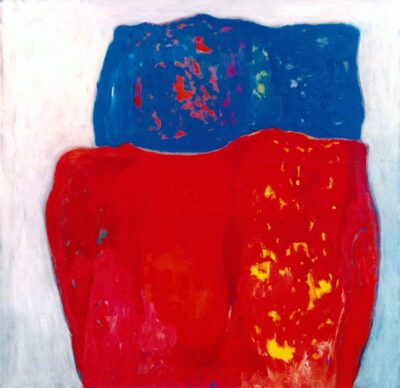

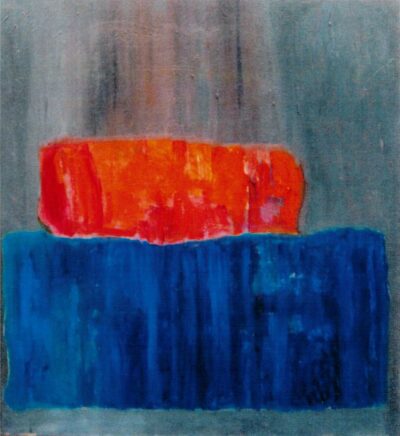

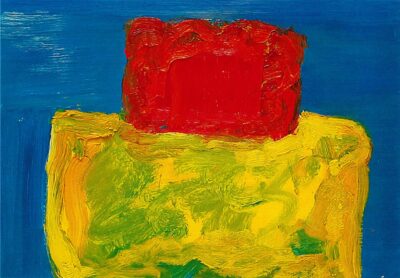

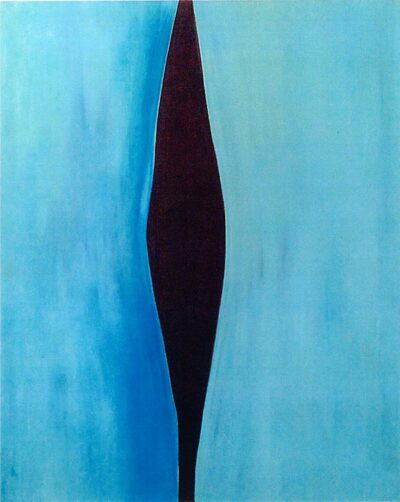

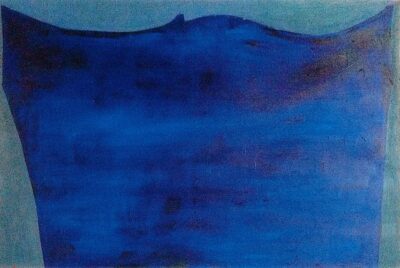

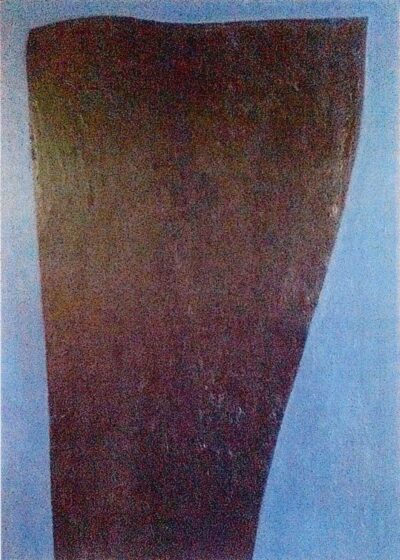

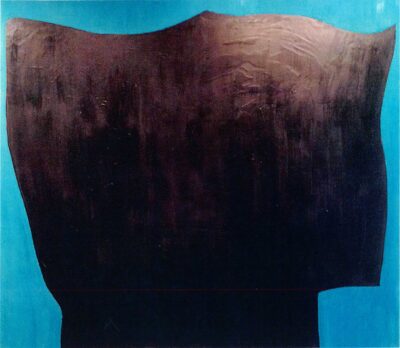

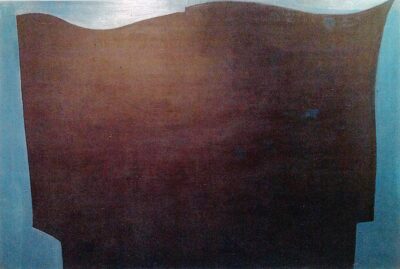

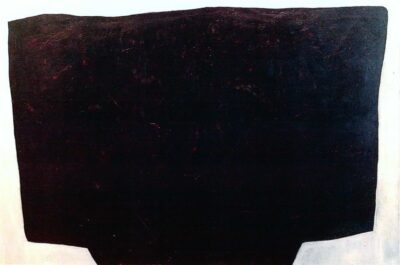

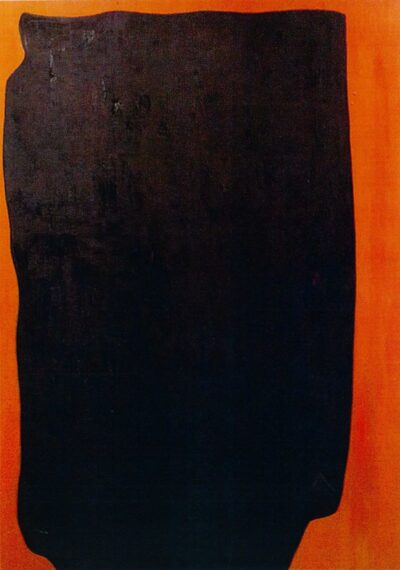

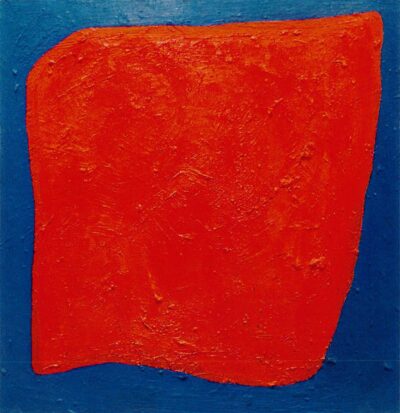

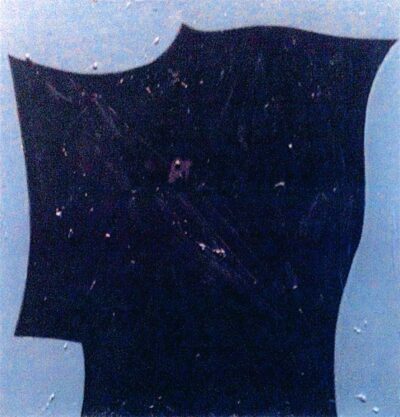

The works that were created in the New York loft studio from 1980 to 2015, approximately, comprise the core of the collection, as well as the most representative sample of the artist’s work.

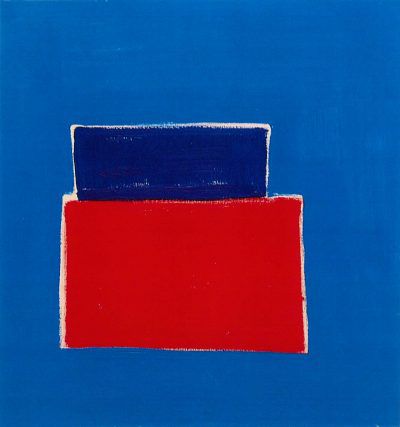

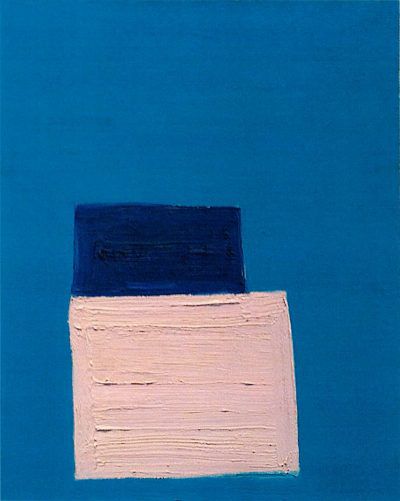

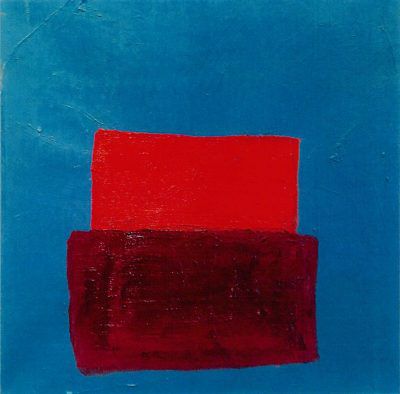

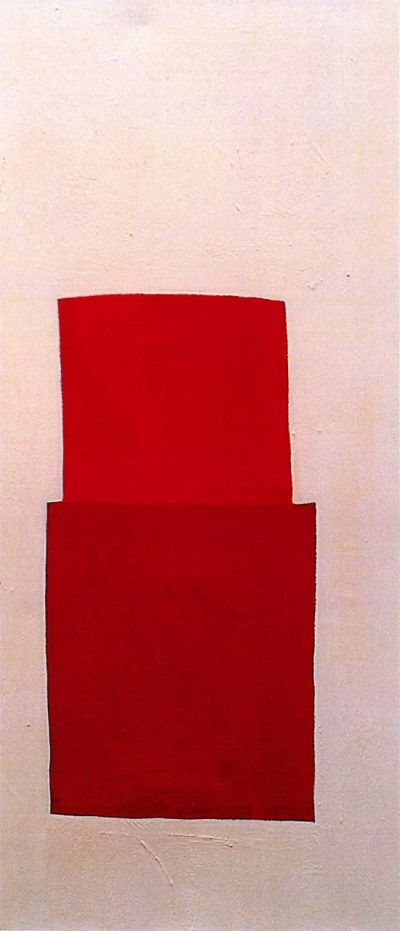

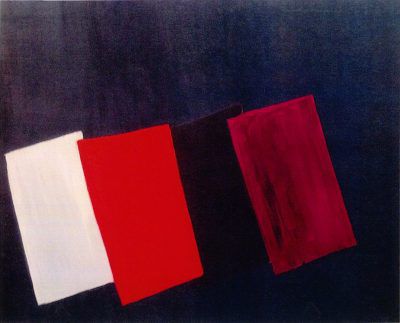

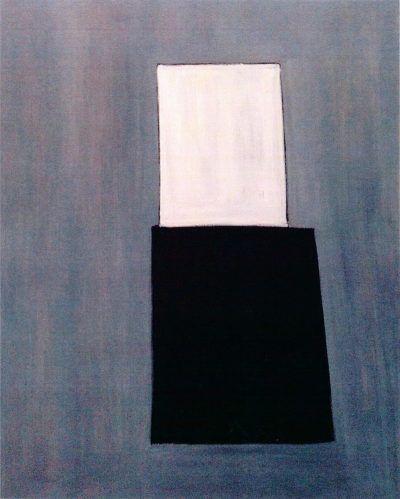

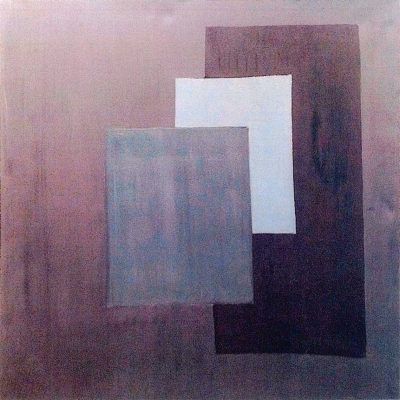

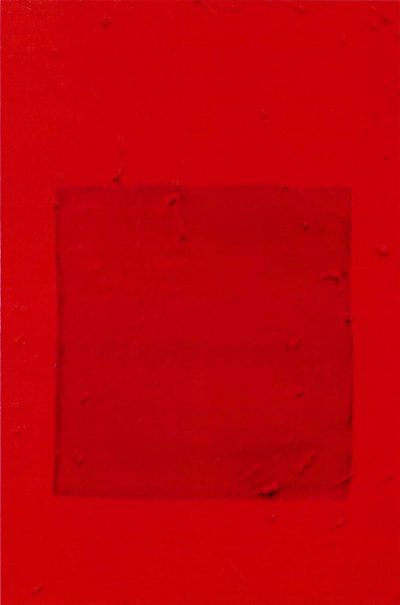

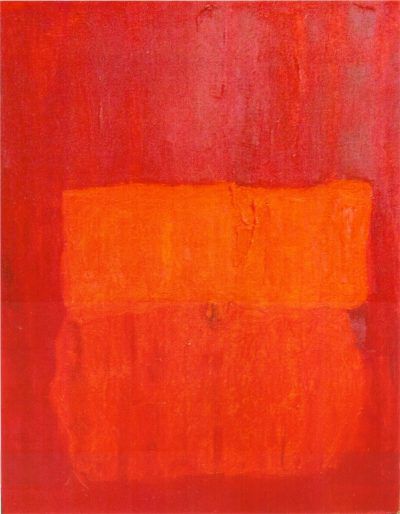

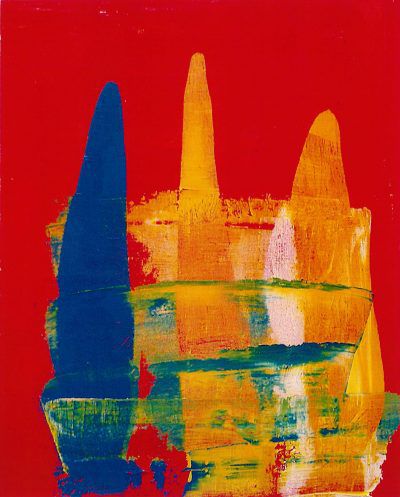

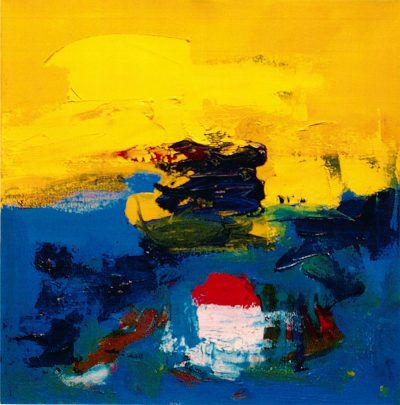

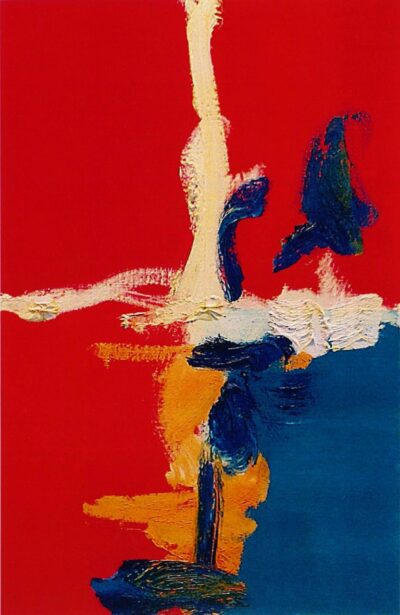

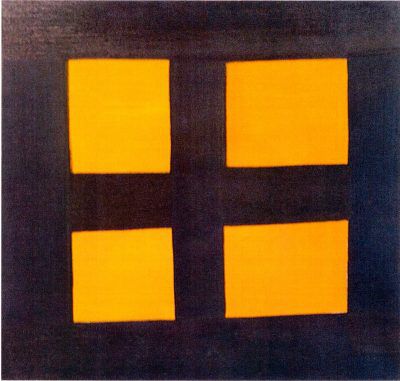

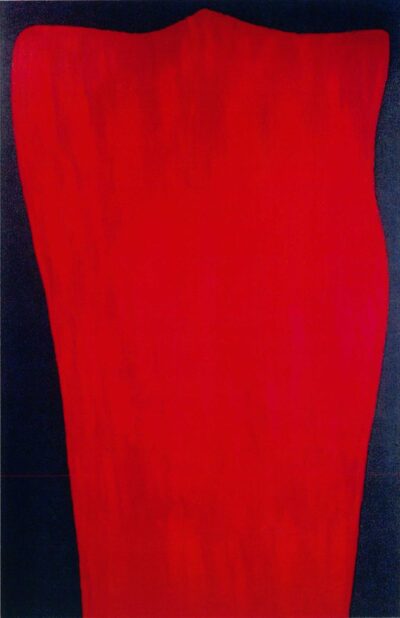

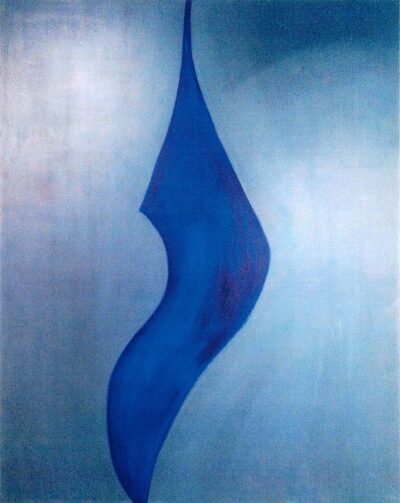

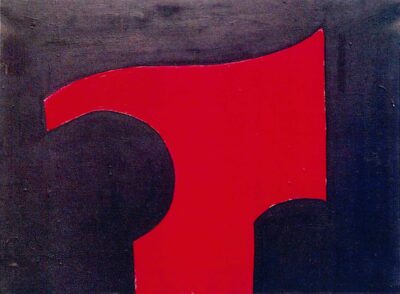

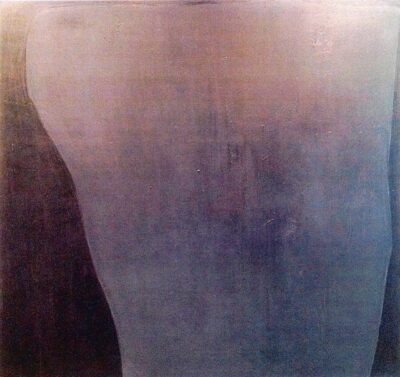

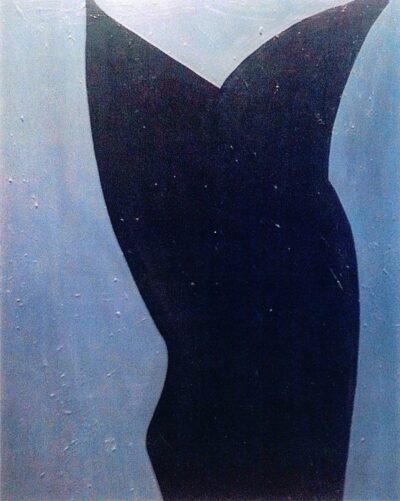

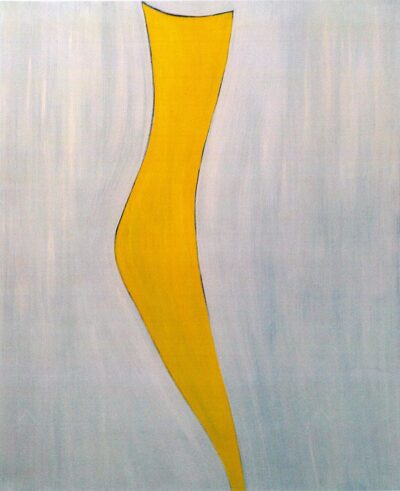

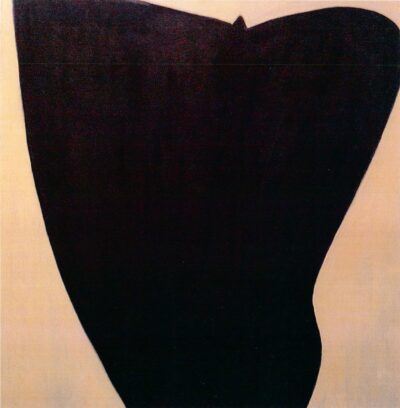

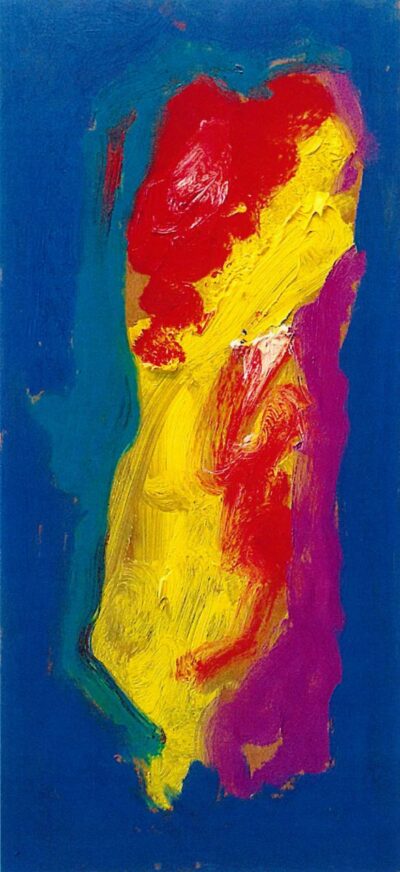

These works are a distillation of all his quests, his influences, his aspirations and his achievements. Even though they span a period of thirty-five years, they maintain a consistency in style, and several common features. To begin with, there is the choice of the large-scale format, which lends the works a monumental quality, as well as providing greater freedom in painting.

The cons of this choice, such as, primarily, the special conditions of installation and exhibition they demanded and, by extension, their limited marketability, given the small number of venues that could accommodate works of this type, didn’t particularly concern the artist. Besides, his relentless exploration of shapes, colours and light found its most ideal ground in large-scale painting.

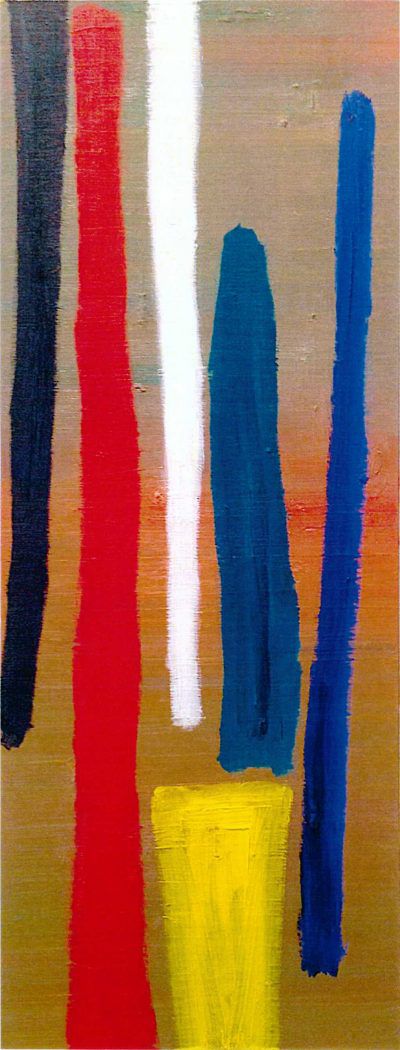

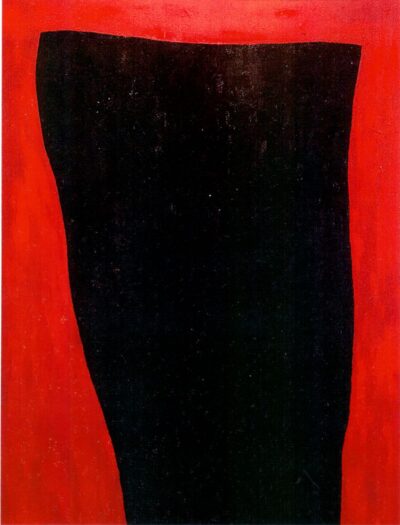

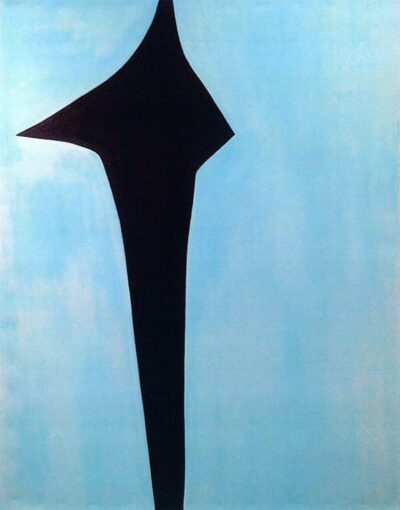

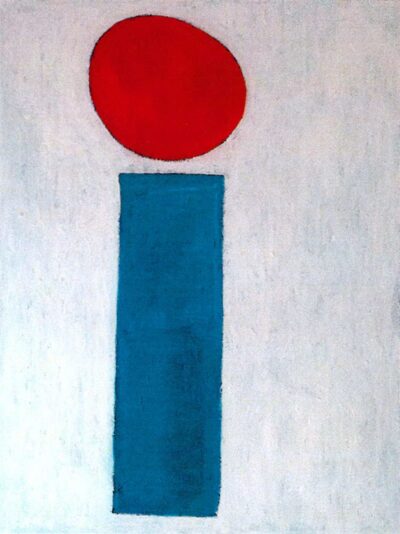

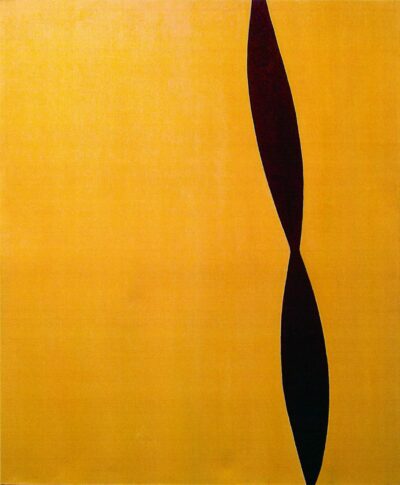

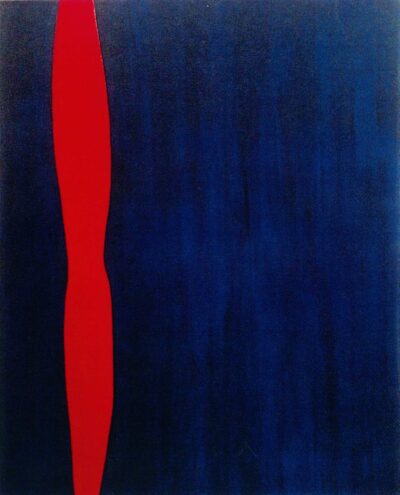

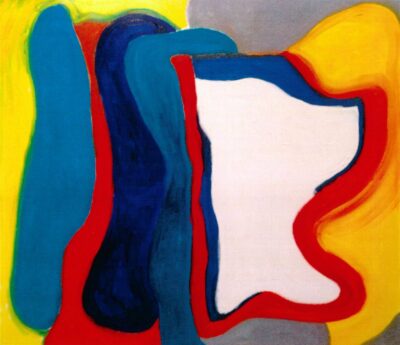

His influences from the painters of abstract expressionism are obvious here. Having seen and studied their work up close, Kapsalis drew elements of their art, as well as practices they employed. Rothko’s painting was a major influence: the power of colour and shape challenges the viewer directly, without any other interventions.

The large-scale format casts the work into an almost human dimension and succeeds in making the viewer part of it. And that, somehow, automatically ignites an emotional explosion that each and every viewer experiences individually, just by being confronted by such a work.

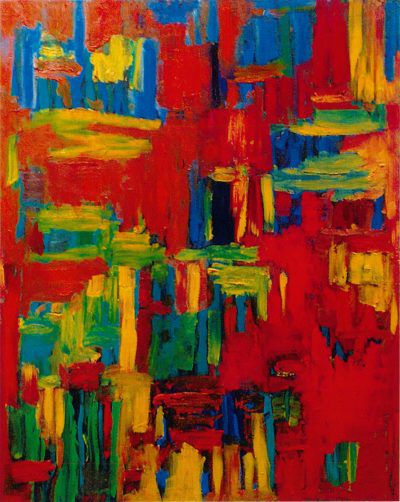

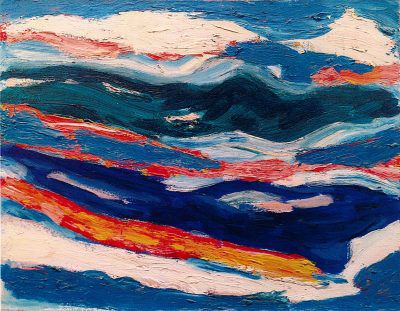

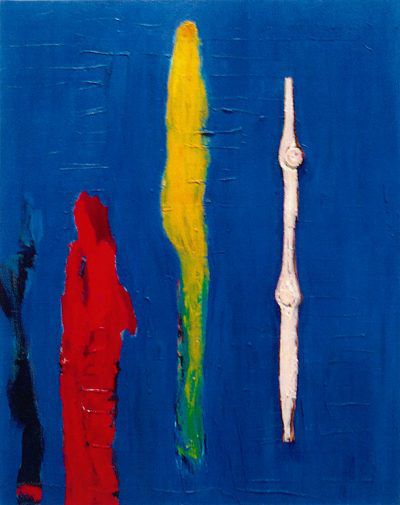

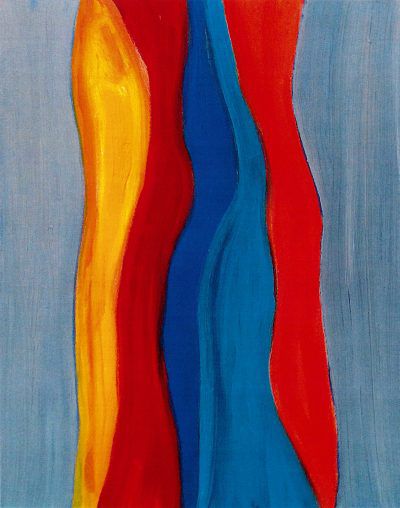

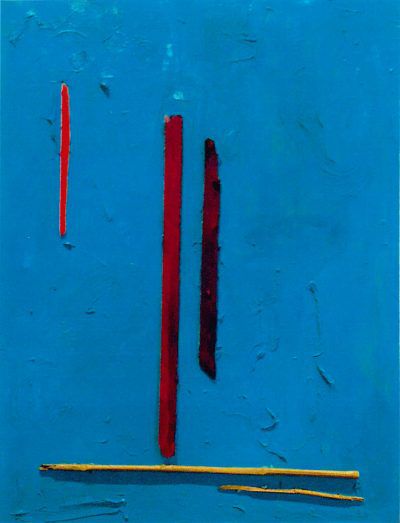

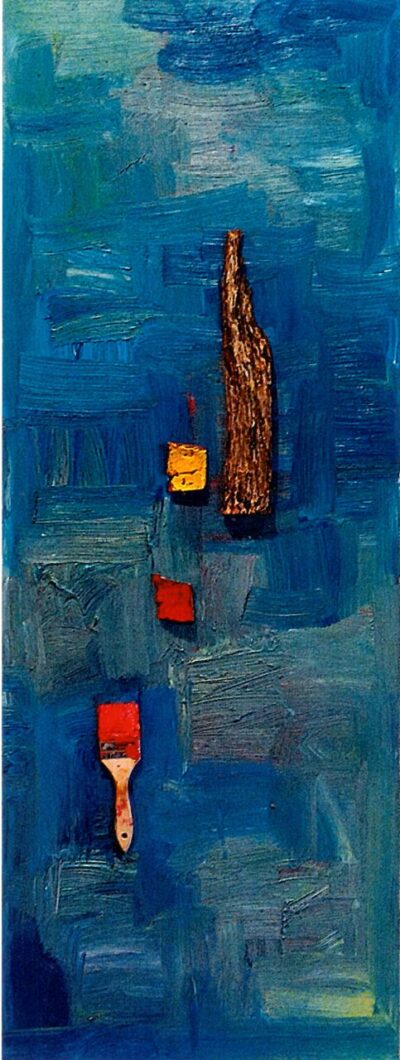

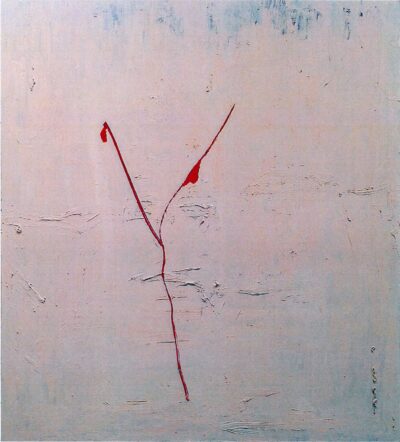

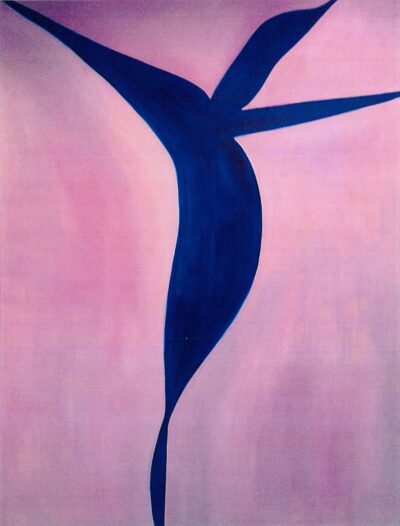

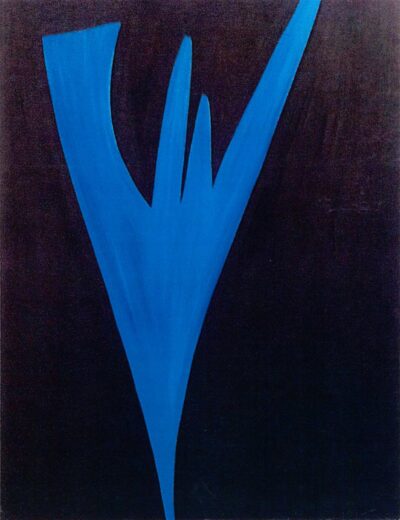

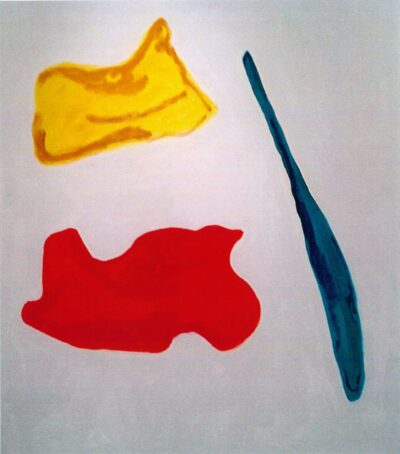

In other works, Kapsalis came closer to Pollock’s gestural painting and his methods, especially that of dripping. He was also well versed in the works of Newman with the large vertical lines, which emulate symbols of worship. Similarities could also even be found, arguably, to David Smith’s steel sculptures.

The works created in the SoHo loft are collectively and undoubtably products of the American post-war painting climate. The emergence of abstract expressionism from the late 1940s and the universal support it received by Museums and Foundations was, in a sense, a one-way street for newer artists, such as Michalis Kapsalis.

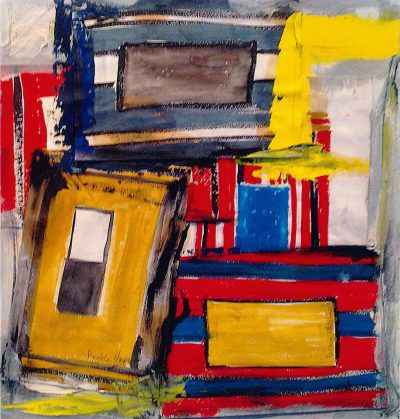

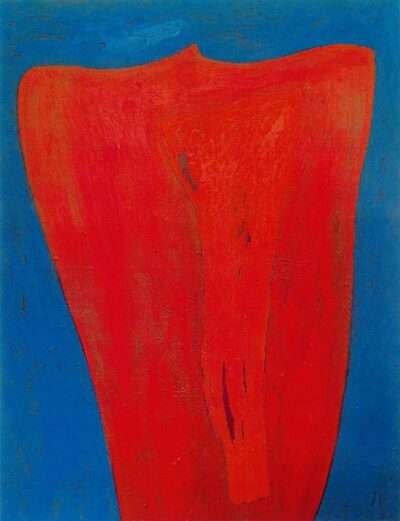

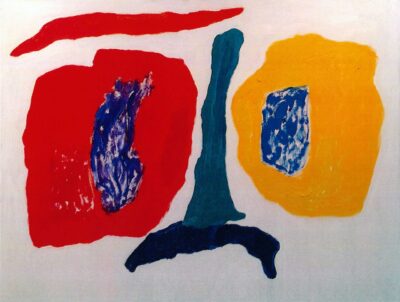

The artist himself had separated his works into smaller themed categories: “Cityscapes and landscapes”, “Gestures and stripes”, “Figures and linear shapes”, “Monoforms and torsos” are some of those that belong in the same artistic and theoretical context as the one mentioned above.

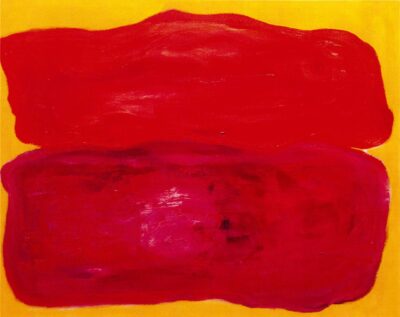

Special reference should be made to the “Poetry and music” category, whose works represent his attempt to transfer sounds and lyrics emotively onto the painting surface. Kapsalis loved music and had the good fortune to see the most important musicians of the jazz scene, at their heyday during the 60s and 70s, performing live at New York’s music stages and bars, with the famous and historic Village Vanguard and Fanelli Café among them. Later, he became a regular at the Blue Note which, ever since it opened in 1981, claimed its place as the quintessential “temple” of jazz. In this series, the free improvisations of music meet their more organised, considered version on the canvas, resulting in works of excellent quality and emotional wholeness.

The Greek works

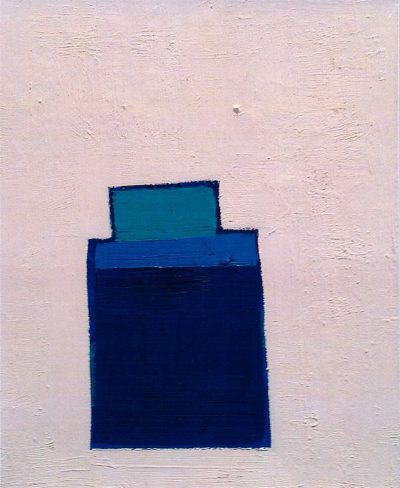

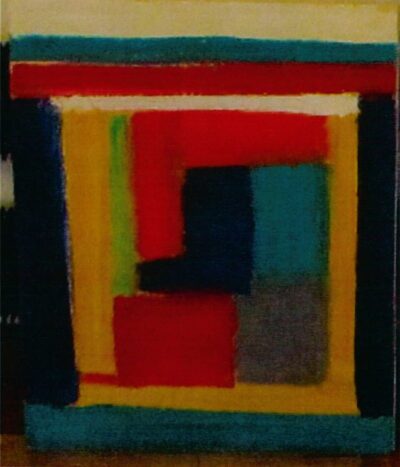

A fairly large part of his work was created in Greece, mainly at his home in Psychiko, where he kept a small studio, as well as in Mykonos. Kapsalis loved the island and visited frequently; several of his – very few, in total – solo exhibitions were held there. Even though these works were made during different time periods, they are generally consistent with the painter’s overall spirit, his attitudes and his stylistic choices.

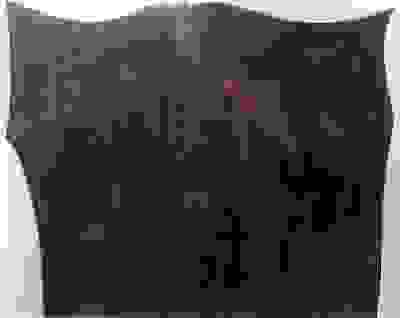

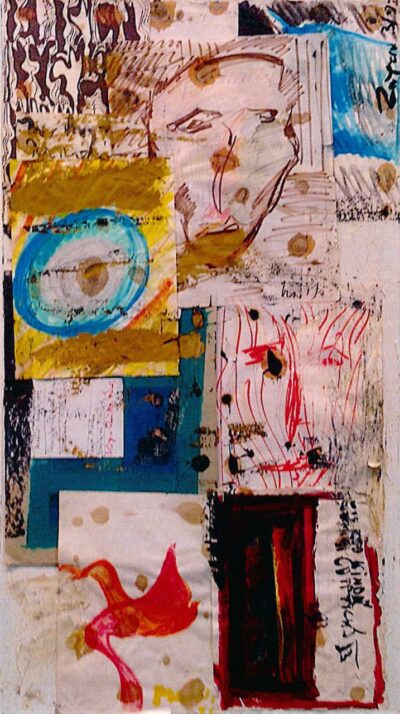

There are, however, certain features that differentiate them from the rest, and which are worth noting. First comes the inscription of Greek words on the painting surface, in a way that alludes to the technique of graffiti, signalling, in a sense, the Greek origin of the works. Sometimes the connection is obvious (in Athens), sometimes latent (esperas, ton taxiarchon) In any case, this is a conscious choice that appears in a small number of works, and is absent in the works created in America.

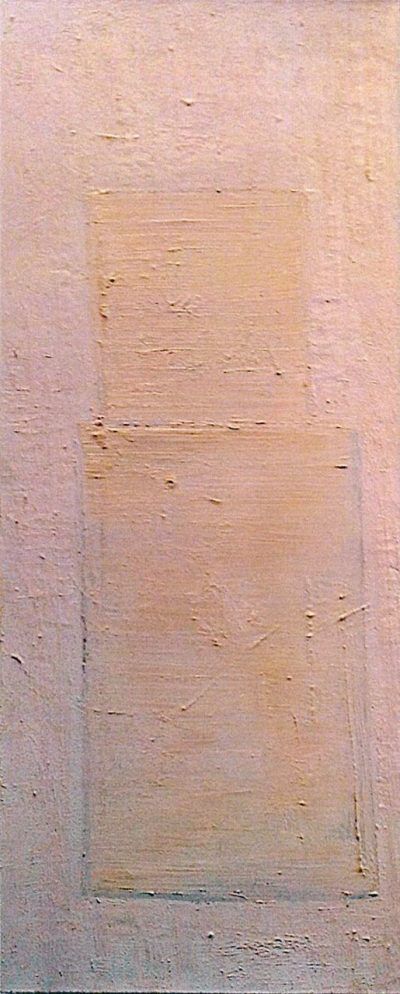

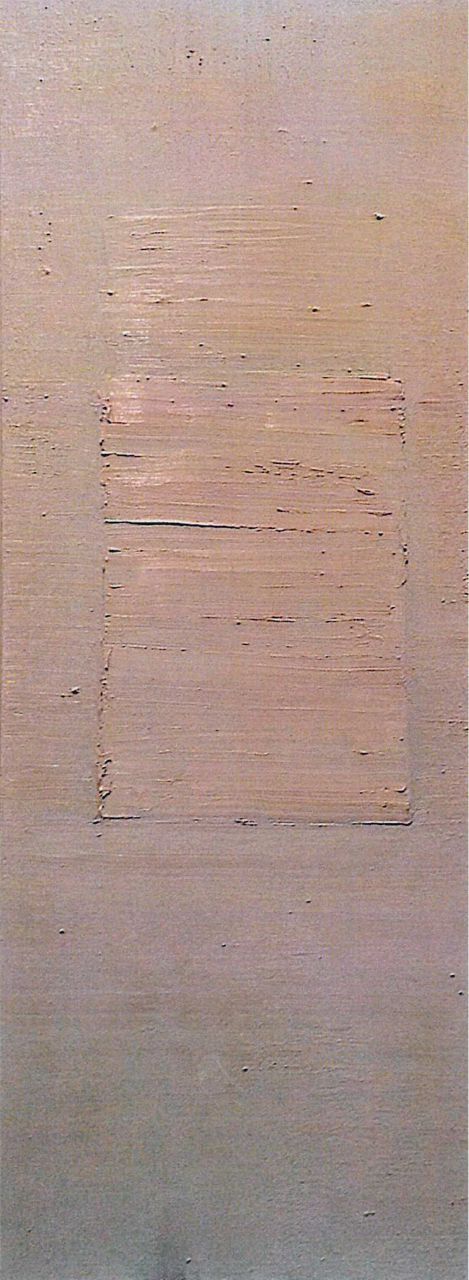

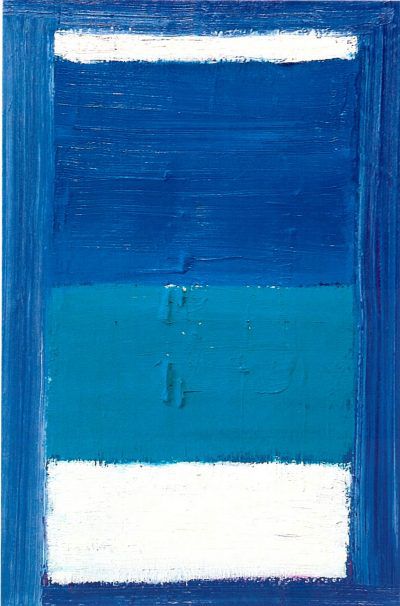

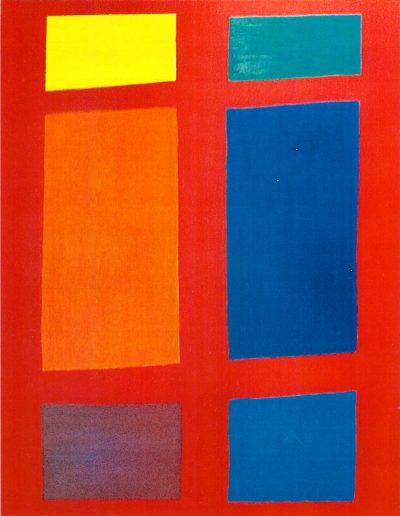

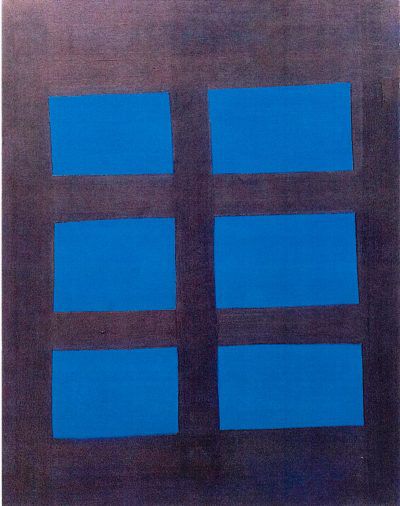

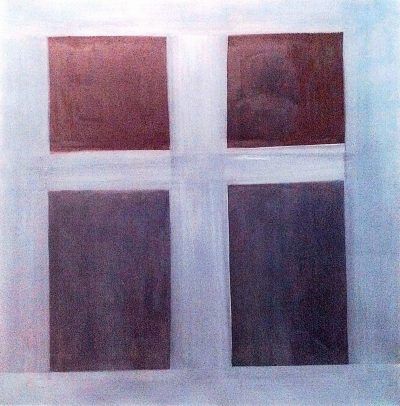

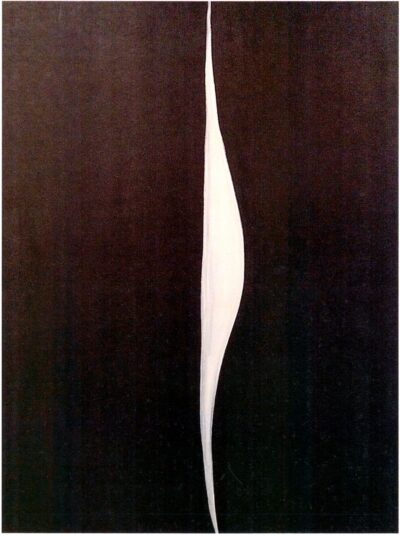

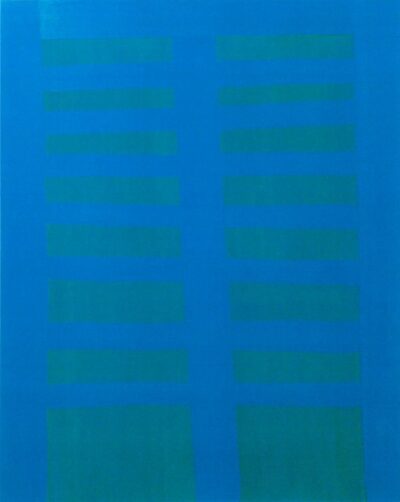

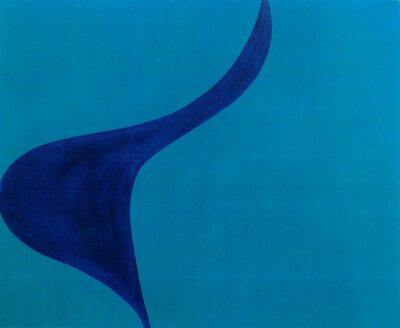

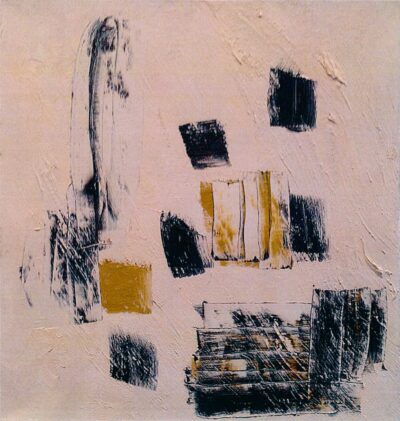

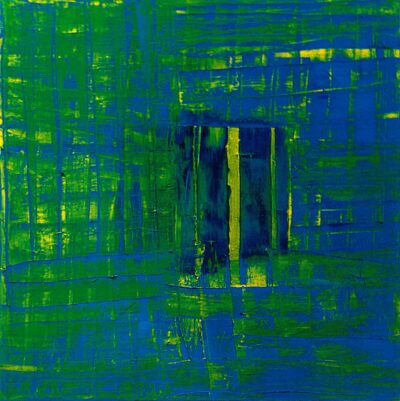

A second, and more substantial observation is connected to the theme of windows. This is a series of works inspired by the windows of Cycladic homes, that outstanding sample of local architecture. But that is not to say that the artist circumvents his fundamental choices. Strict geometric simplicity meets Donald Judd’s minimalism, and a classic Greek feature gains a new dimension, as it is depicted from an entirely different angle.

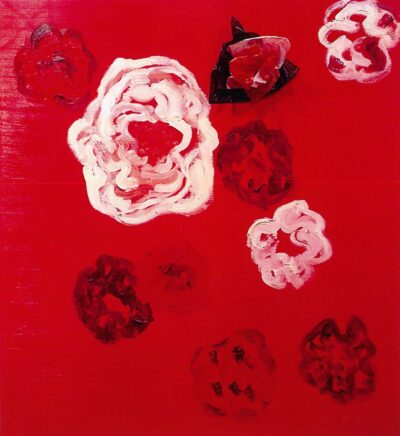

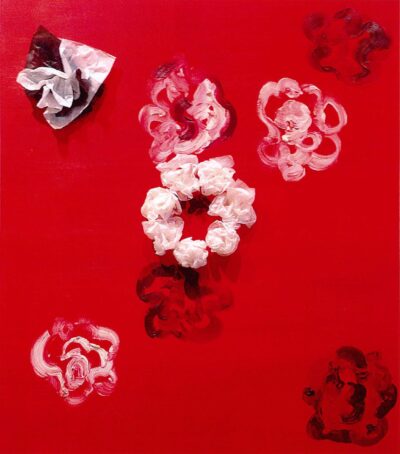

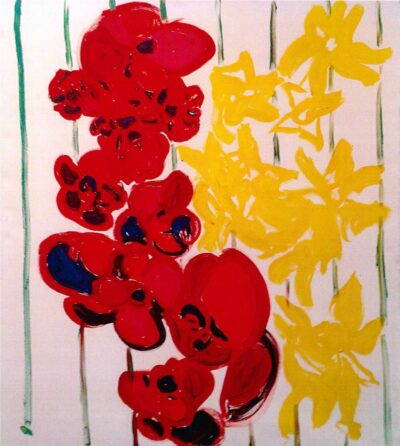

“Figurative” works

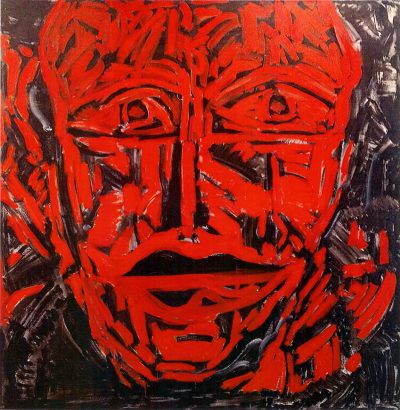

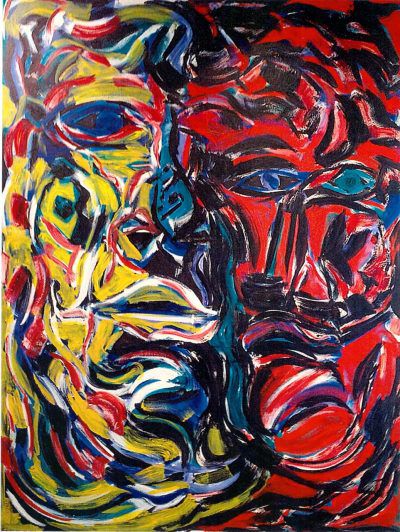

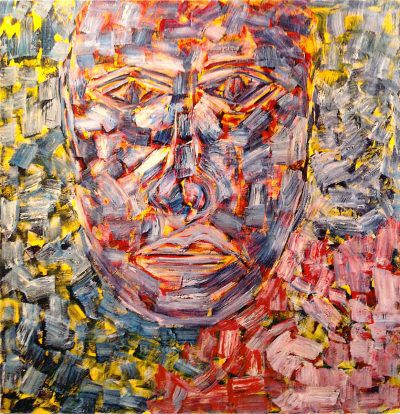

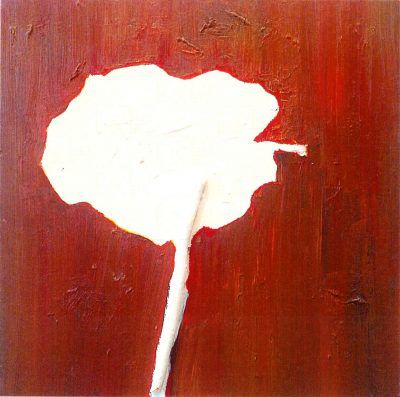

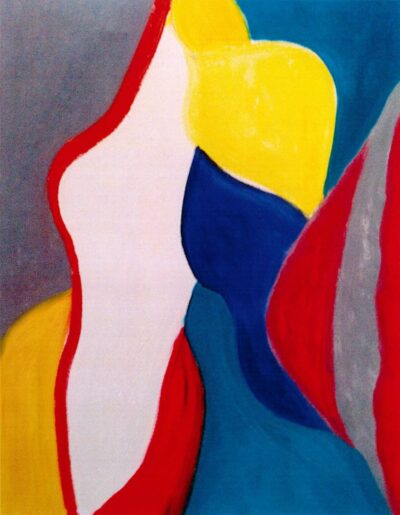

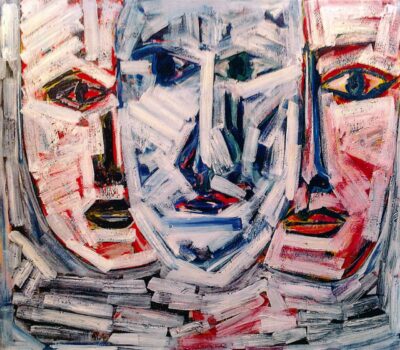

To apply this term to an artist who worked almost exclusively in abstract painting is arguably an exaggeration. There are, however, several works with recognisable features, which reveal another source of interest and distinct influences. This category includes a series of floral paintings, most likely created at the Athens studio and in Mykonos during the 1980s. During that same time period, Kapsalis also painted a series of heads that refer directly to primitive forms of African painting.

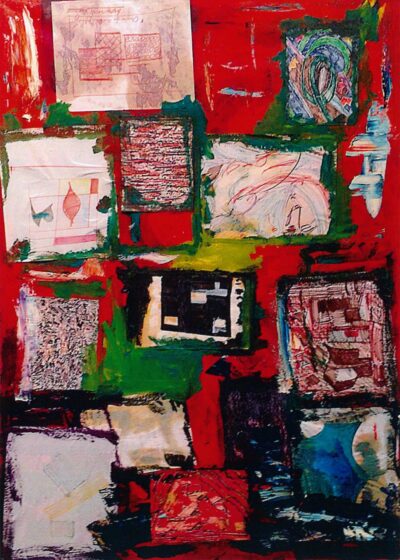

There are, however, certain more “complex” works as well, which bear obvious traces of the influence of Jean Dubuffet’s primitivism in particular, and the quests of art brut in general: violent alternations of colour, agonised facial expressions and a total coverage of every part of the painting surface in an almost anxious way are characteristic of this period of Kapsalis’ painting. In these works, Kapsalis doesn’t merely alter his established technical preferences, but instigates a dialogue with an entirely different view on art itself, its meaning and its impact, placing the human condition at its core.

Even though he did not develop this part of his work any further, it still stands as an important indication of both his potential as a painter, and his sensibilities.

In summary, it would be fair to say that Michalis Kapsalis Achieved a successful combination of technical and theoretical knowledge of painting and its movements, and his own broadness of spirit and personal talent. His multifaceted work, which is slowly unfolding, is deserving of more extensive study and research, so that it may claim its rightful place in the history of art.